The Best Way to Use AI for Learning

An effective method of learning complex knowledge with AI.

This article is written by Alan Chan, Co-founder & CEO of Heptabase.

Foreword

I’ve always been confident in my ability to learn. In high school, I ranked among the top 10 in the National Physics Olympiad team. In college, I received the Presidential Award while completing PhD-level courses as a freshman. Later in my career, I founded a startup and taught myself everything necessary to build software products and scale a business that now serves customers in over 100 countries. Through all of this, I never felt the need to change the way I learned — it was effective and reliable.

However, the rise of AI has changed everything. I realized that while my original learning methods were effective, they could now be elevated to an entirely new level. Many people use AI to boost learning efficiency — for example, by summarizing dense material into concise bullet points or translating foreign texts into their native language — essentially allowing them to do what they were already doing, only faster. But I noticed that these efficiency gains, when accumulated, reveal a deeper transformation: learning methods that once felt too time-consuming to attempt have suddenly become feasible. As a result, I think the most important question to ask is not “how to learn more efficiently,” but “how to become capable of learning knowledge that is more complex, abstract, and challenging.” At the end of the day, I believe the value of learning does not lie in accumulating as much knowledge as possible, but in cultivating the ability to think more deeply about important questions. And often, those most important questions are also the ones that demand the hardest and most challenging knowledge.

Consider the case of learning quantum mechanics. Reading the best academic textbook might take 200 hours — something you could never justify if you only had 20 hours to spare as a working professional. In the pre-AI era, you’d probably have spent those 20 hours on popular introductory books, YouTube videos, or web articles. With AI, you now have two options:

Use AI to consume a much larger volume of the same lighter material — dozens more popular books, videos, and articles — in those 20 hours.

Use AI to engage directly with the best academic textbook in the field for 20 hours.

I’d argue the first path leads to diminishing returns, whereas the second — though it won’t enable you to finish an entire textbook — can open the door to deeper understanding within a manageable timeframe. And in an era where misinformation spreads so easily, I believe engaging with primary sources is more valuable than ever.

In this article, I’ll walk you through how I’ve been using AI to teach myself a textbook step by step. With its help, the gains in both the depth and quality of my learning have been mind-blowing, and I want to share that excitement with you.

The book I’ve chosen is Pattern Recognition and Machine Learning (PRML) by Christopher Bishop — a 710-page classic available as a free PDF from Microsoft Research. I chose this book because it’s aimed at advanced undergraduates or first-year PhD students, making it somewhat challenging for those outside the field. For this demonstration, I’ll focus on just the first 32 pages. Although my example comes from computer science, the approach I’ll outline applies to any dense, long-form source in any domain.

In the appendix, I’ll also show how you can use AI to decide which books are worth your time, and I’ll share some excellent websites that provide textbooks legally and freely online. Believe it or not, there are a huge number of extremely high-quality textbooks available in PDF format — many released under open-access and considered among the very best.

The Tools You’ll Need

Before I explain how I use AI for learning, I want to outline the core elements required for this process:

A PDF file of your learning source (see appendix)

A high-quality PDF parser with OCR that can extract text, images, tables, and equations.

Access to an AI model

A digital whiteboard with note-taking features

You don’t necessarily need all of these to benefit from AI-powered learning. However, the more of them you have, the more they compound your ability to learn — something I’ll demonstrate shortly.

In this article, I’ll use Heptabase as my tool of demonstration. The key reason is that I built this tool with my team specifically to enable this kind of learning method. It already integrates all the elements above, so the only thing you need to bring is a PDF file.

Method Demonstration

Step 1: Parse the PDF

When you have the PDF file of your learning material, the first step is to parse it. While most AI tools allow you to ask questions about a PDF, parsing offers significant benefits. Without parsing, most AI models don’t actually read the entire PDF as context. Instead, they only process portions they consider “relevant” to your question — and their method of determining relevance (usually based on RAG) is far from perfect.

By parsing the PDF, you gain control over which parts the AI must use as context. This dramatically improves reliability and accuracy. For example, you can ask questions based on a specific page range or hand-picked paragraphs. You can also ask the AI to translate or summarize selected ranges without worrying about losing important content.

Here’s how it works in Heptabase: simply press the Parse button in the top-right corner, and you’ll be able to prompt your AI with precise control over your PDF.

One important note: if the content is very long (>30k words), you’ll need to enable MAX mode. This ensures you can take advantage of the full context limit of your AI model. Modern AI models support extremely large context windows — around 400k to 1M tokens, which is roughly 300k–750k words. For reference, The Lord of the Rings trilogy is about 480k words. That means you could upload the entire trilogy into chat, and the AI would still be able to see and remember everything.

Step 2: Create the Learning Materials

After parsing the PDF, the next step is to prepare learning materials and place them on the whiteboard. You might wonder: why not just read the PDF directly and discuss it with AI as you go? Of course, you can — but for longer works (such as a 710-page textbook) that require extended reading and deep thinking, I believe there is tremendous value in preparing learning materials in advance (I’ll explain the detailed reasons in Steps 3 and 4). The simplest approach is to copy and paste the content into cards, then arrange those cards from left to right on the whiteboard following the book’s order. Typically, I let each card represent one chapter; if a chapter is too long, each card can instead represent a section within the chapter.

However, if the book is difficult for you to read — for example, if it’s written in a foreign or ancient language, filled with technical terms, or assumes a level of prior knowledge you don’t yet have — a great option is to ask AI to generate different types of learning materials based on this content and place them on the whiteboard.

What exactly should you generate? That depends on you — the learner. A good rule of thumb is to reflect on two things: your strengths and weaknesses as a learner, and the nature of the material you’re studying.

Example 1. I read English at a normal speed, but I read Traditional Chinese very fast since it’s my native language (I’m from Taiwan). However, when it comes to names and technical terms, I process them much more quickly in English. To make the most of this, I usually ask AI to translate the text into Traditional Chinese while keeping all names and technical terms in English.

Translate all content into Traditional Chinese word for word, without omitting anything, and make sure it reads smoothly for Chinese readers. Keep personal names in the original language, and provide both Chinese and English for technical terms or proper nouns (as long as readability is not affected). Do not break the translation into parts just because the content is long. I want you to complete the entire translation in one go. Don’t worry about the output being too long, and make absolutely sure not to miss a single sentence.

Example 2. When studying history or the humanities, I like to start with the big picture — understanding the author’s main message — before diving into details. In these cases, I usually ask AI to generate a summary tailored to my needs before I read the original text. This summary acts as a “compass” in my mind, guiding me as I explore the specifics.

Here’s an example of the kind of prompt I might use:

Summarize Chapter [X] for a reader who has not read it yet. Focus on the main ideas, arguments, and themes, showing how they build on each other. Highlight the central questions the author is addressing, and explain the logical or narrative flow so the reader understands the mental structure of the chapter before reading. Keep it accessible, while preserving the depth of the author’s perspective.

Interestingly, summaries are much less useful for mathematics. Learning a new math topic is more like learning a foreign language: you don’t benefit much from summaries because real understanding comes from working through definitions, structures, and proofs. What’s more helpful is a list of key definitions, each with an intuitive explanation, along with a set of guiding questions that spark curiosity and motivation before tackling abstraction.

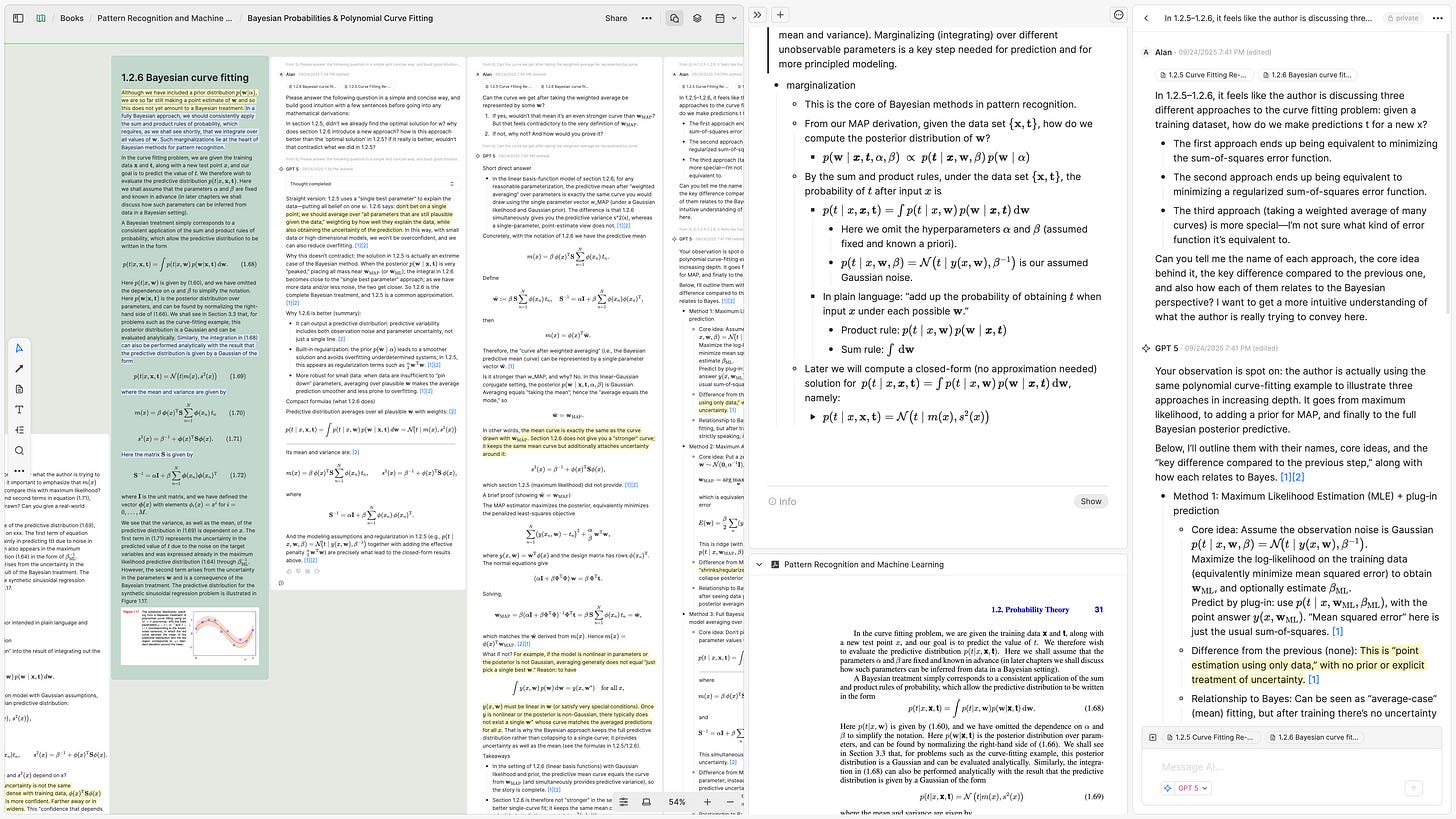

Once you’ve generated these materials, place them on the whiteboard. In my demo, for example, instead of using the original content, I asked AI to translate the first 32 pages of the textbook and split them into eight cards (the green ones), each representing a section or major subsection.

I also asked AI to create summaries for each section, including the key definitions, equations, and conclusions I cared about. I then dragged these summary messages (the white ones) onto the whiteboard and placed them next to the translated cards, so I could read the summaries first before diving into the details.

Step 3: Read from the Whiteboard and Discuss with AI

Now that I have the translated cards and summaries laid out on the whiteboard, sorted in textbook order from left to right, the setup itself is already extremely useful. It means I can see 32 pages of a textbook at a glance.

Why is this useful? Traditionally, whether I’m reading physical books or ebooks, the most frustrating part is the effort and delay of moving across pages. Suppose I’m on page 105 and realize a concept connects to something I read earlier (say, on pages 79 and 87). To “connect the dots,” I have to flip back and forth, which takes several seconds and could break my flow. What’s worse is that I can’t view those different pages side by side!

With 32 pages spread out on the whiteboard in front of me, however, all I need to do is shift my eyes to locate a highlight I made earlier. That takes only milliseconds, which means I can do it frequently without interrupting my flow of thought. I was surprised by how such a small difference — seconds versus milliseconds — can have such a big impact on focus and reading.

One point I really want to emphasize is that this may be the most valuable role the whiteboard plays in my learning process. Many people think of whiteboards primarily as visualization or diagramming tools. They see themselves as either “visual thinkers” (using arrows, mind maps, and diagrams) or more symbolic thinkers (expressing ideas through essays or code). I believe this dichotomy misses the point.

The true nature of a whiteboard is that it’s a giant, borderless desk. Whether you consider yourself a visual thinker or not, everyone needs a desk. The size of your desk determines how much information you can see at once, which in turn influences how far your thinking can reach. Of course, smart people often have a large “virtual desk” in their brains — their working memory, the amount of information they can hold at a given time. But whenever you’re dealing with problems that exceed that mental capacity, a giant desk, a big screen, or an infinite whiteboard that can hold large amounts of information becomes one of the most powerful tools available. It frees you from the tiny rectangle of a physical book or e-reader.

Back to the setup: Once I’ve arranged the book’s contents as cards on the whiteboard, I begin reading and highlighting. Nothing unusual so far. The main benefits at this stage come from the combination of translation, summarization, and the information density of the whiteboard. But here’s the most important part: whenever I get stuck and want to ask the AI a question, it already has all the context.

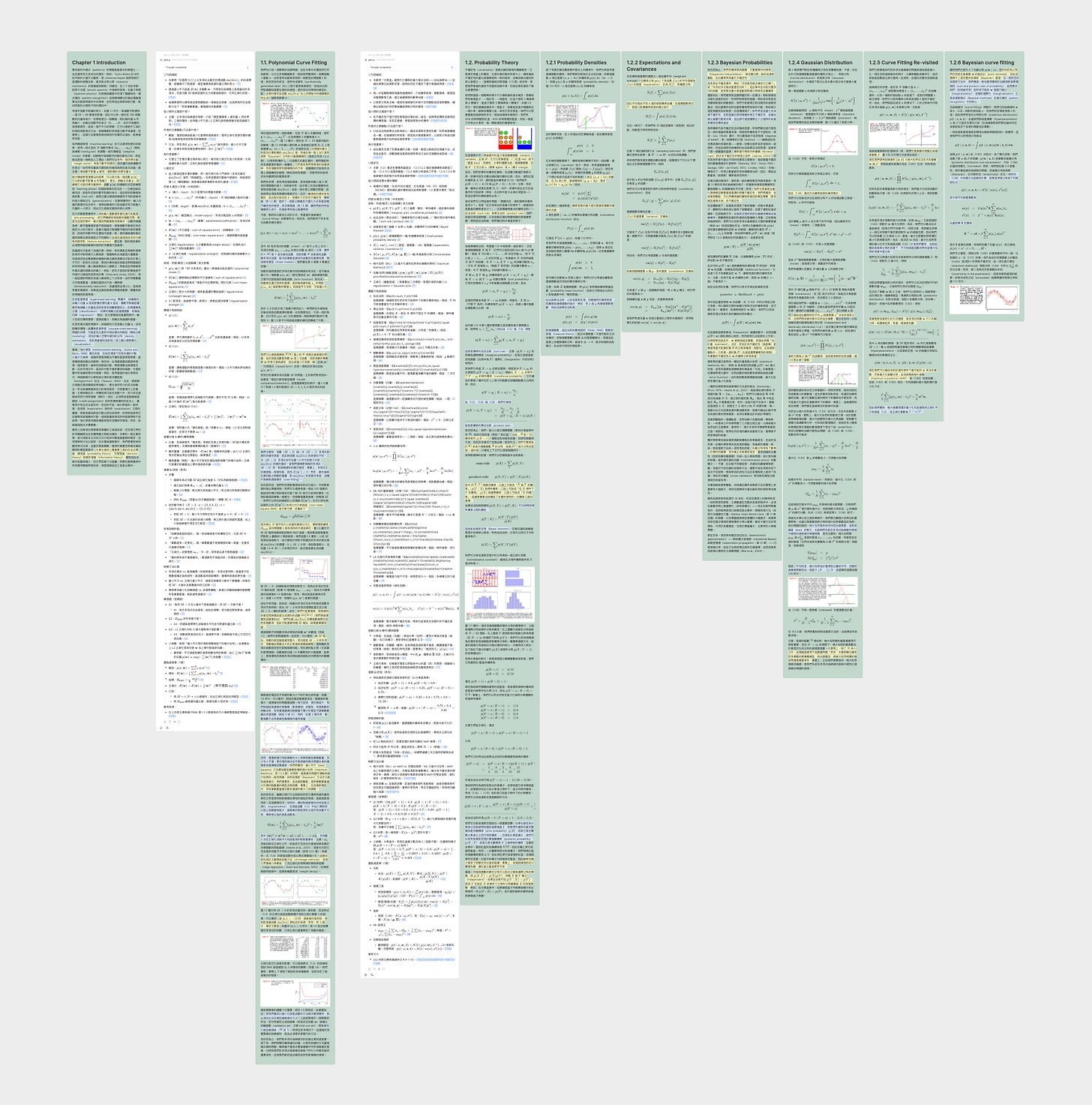

For example, when I was reading the card on Gaussian distribution, one passage in it left me confused. At that moment:

I could right-click the card to start a chat with AI, quote the confusing passage, and ask it to explain. The AI would answer my question using the full content of the card as context.

I could ask the AI to give me a simple, concrete example to explain that passage, or to design a hypothetical problem and solve it using the knowledge described there.

I could share my current understanding of the passage with the AI, ask it to judge whether I was correct, and even have it quiz me to test my comprehension.

I could even have the AI read the original textbook PDF, so that with the full context it could tell me what the author intended in writing that passage, and whether those details would become important in later chapters I hadn’t yet reached.

It feels like carrying around a professor who has already read the entire book — and if the first answer I get isn’t ideal, I can simply rephrase the question and get a better explanation.

I’ve recently started using this method to read several textbooks, and oh god, I really wish I’d had this tool back in college. In the past, whenever I got stuck on something in a textbook, I usually had to wait until the professor’s next office hour to resolve it. Now AI helps me immediately get past every obstacle I encounter while studying.

Another powerful aspect of combining AI with the whiteboard is that I can drag the AI’s replies directly onto the board, placing them beside the cards I translated from the original text. At any time, I can then have the AI read the entire whiteboard — not just the textbook content, but also the chat history I’ve added — so it gains a clearer sense of my current understanding.

The whiteboard — now filled with the translated textbook content (green cards), summaries, my highlights and notes, and my entire Q&A history with the AI (white messages) — serves as an infinite desk that keeps my complete learning context visible at every step. So if I studied for two hours yesterday and want to continue today, I can instantly get back into the flow just by glancing at the whiteboard and seeing exactly where I left off.

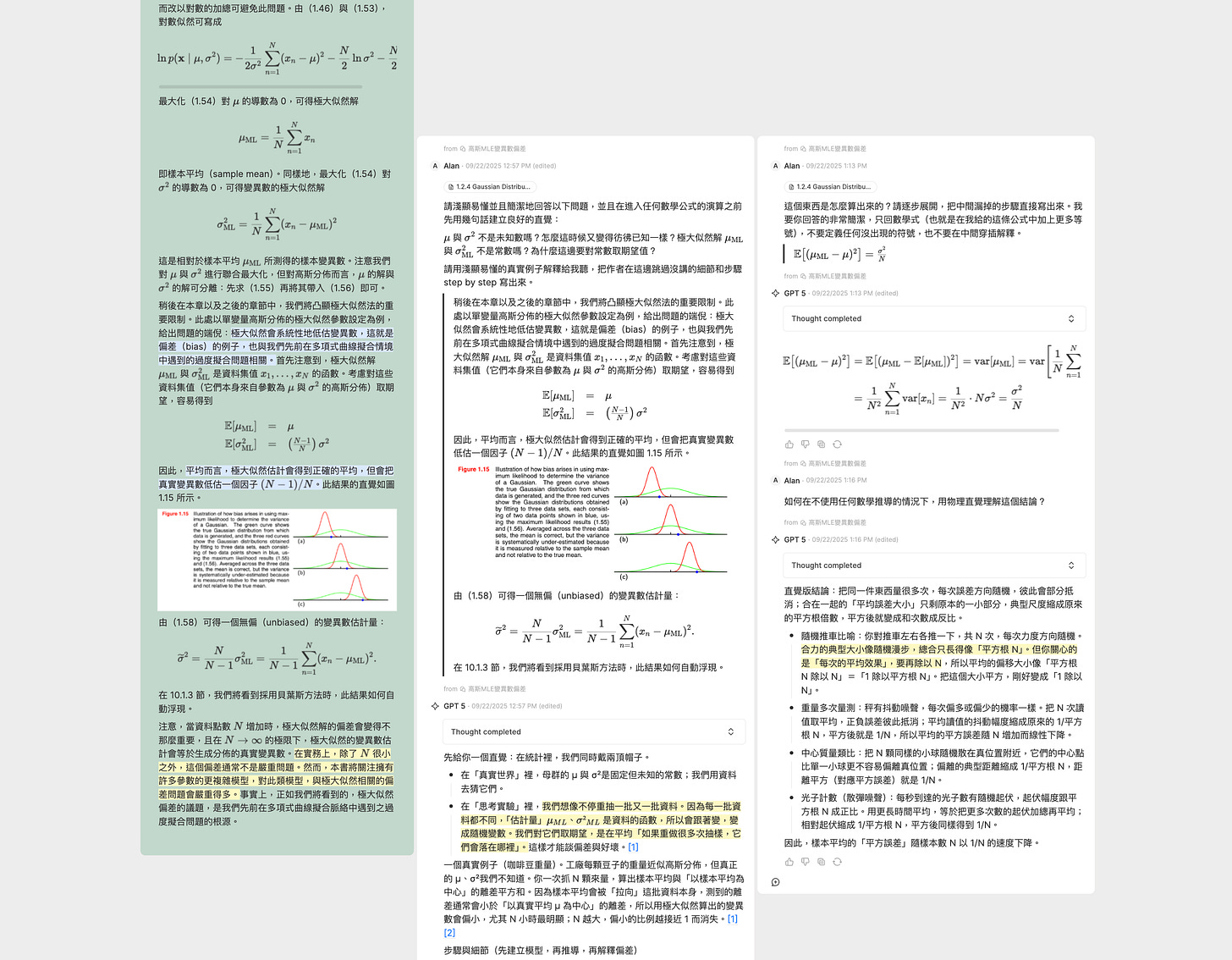

Step 4: Take Notes in Your Own Words

Let’s say I spend two hours reading today (as in Step 3). At the end of my reading session, while everything is still fresh in my mind, I always take notes. My note-taking style is fairly simple: I start with a blank note and try to rewrite everything I’ve learned in my own words, as if I were teaching it to someone else. This process helps me spot and fill in logical gaps I hadn’t noticed while reading. It’s similar to what some of my professor friends do when they want to learn a new field — they do it by teaching a course.

That said, “writing in my own words” isn’t entirely accurate. What I actually do is place a blank note in the side panel so I can view it alongside the whiteboard. I then copy key content from the whiteboard that I find important or inspiring — whether from textbook content cards or AI messages — and paste it into my notes. From there, I edit and reshape the material into my own narrative. For example, when studying PRML, I obviously don’t have time to retype every LaTeX equation. Instead, I copy and paste them (sometimes with edits) and then add my own explanations beneath.

A crucial part of this editing process is organization: I arrange my notes into a nested bullet-point hierarchy for each topic. This helps my mind form a clear sense of how knowledge is structured and connected. At the same time, it forces me to think critically about which content is truly important and worth keeping — and which can be deleted.

So, my daily reading sessions essentially follow a loop of Step 3 → Step 4: read, ask, take notes, then repeat. After a few days of doing this, once I’ve accumulated enough notes — say, an entire chapter or two of a textbook — I move on to Step 5 to synthesize them.

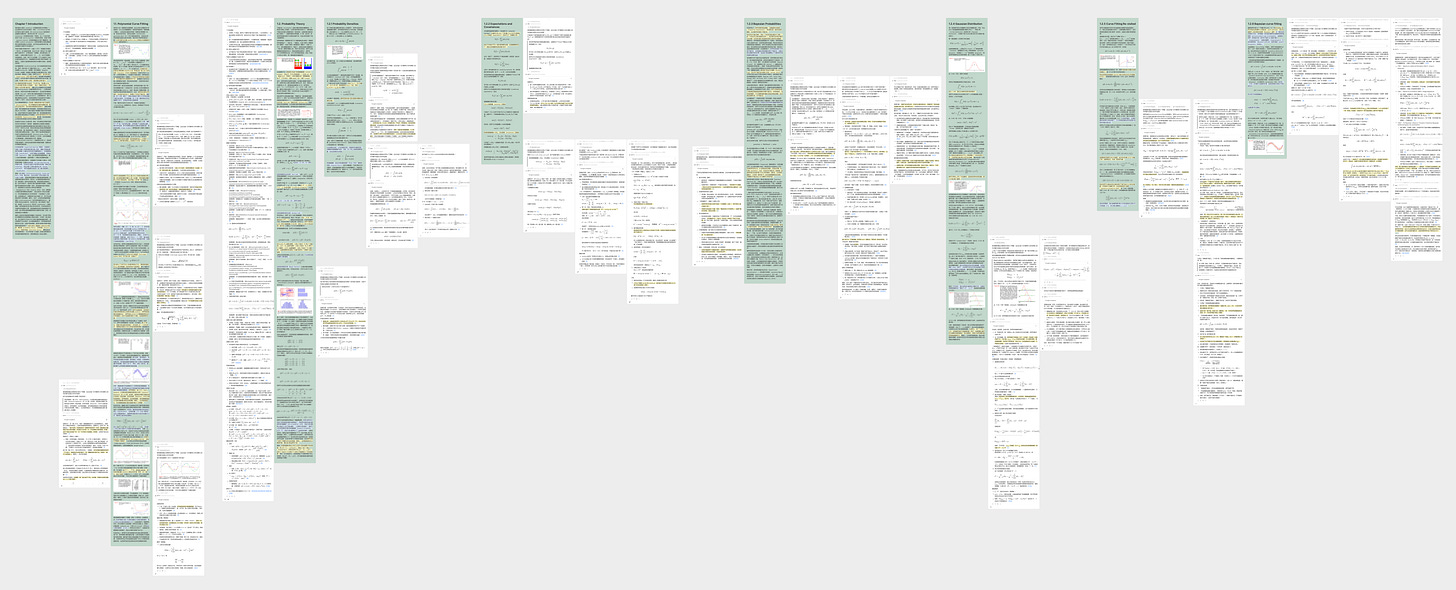

Step 5: Visualize, Synthesize

A few years ago, I wrote an article called The Best Way to Acquire Knowledge from Reading, where I explained this step in detail. I won’t repeat everything here, but here’s the short version: when my notes grow really long, I spend time breaking them down into smaller parts and visualizing their relationships. I find this process extremely useful for developing a deeper understanding of what I’ve learned. This is also the stage where drawing arrows and connections becomes really helpful.

By breaking down and visually reorganizing my notes on a whiteboard, I not only clarify the material within one book but also make it easier to synthesize ideas across different books and papers. This is especially valuable when I’m not just learning but also conducting research in a domain.

Conclusion

Now we can look back at the entire process. As shown in the screenshot, the large green area on the left represents my learning materials and discussions with AI. After finishing the day’s study, I always record my notes on the same card — the yellow one in the middle. Once that card accumulates enough content, I break it down into smaller cards and visualize them, which forms the blue area on the right.

The integration of the PDF parser, whiteboard, and AI allows me to maintain an deep state of flow while studying and thinking through advanced materials. And I believe this is only the beginning — through this learning process, I’ve noticed that Step 2, Create the Learning Materials, can actually be automated in many ways by developing AI Agent capabilities. As AI advances and features evolve, we’ll get closer and closer to an “AI tutor” that can take even the most advanced textbooks and teach them to you directly on the whiteboard — and that is truly exciting!

Many people say AI is a hype. Many argue that using AI too much is “outsourcing thinking,” making people worse at it. My experience is the complete opposite. For me, AI enables me to engage with harder materials and spend more time thinking. It’s the best teacher and thinking partner I could ever ask for. And believe me or not — I have very high standards for what makes a great teacher.

Learning is one of those domains where “outsourcing” is meaningless. Having AI solves 100 math problems for you won’t make you better at math. But having AI gives you hints when you’re stuck on those 100 problems can keep you persistent and motivated. In the end, you decide how to use the tool.

When I started Heptabase, my dream was to create the ultimate tool for learning and research — a tool that would let me explore any subject I’m curious about, no matter how complex. That’s why our website has always carried the slogan: “Make sense of complex topics.”

On the surface, Heptabase may look like a whiteboard and note-taking app. But beneath that, every feature has been carefully designed for one purpose: helping people process dense, difficult knowledge. Over the past few years, we’ve built many features toward this vision. Yet only with the recent breakthroughs in AI have I felt we are truly on the verge of fulfilling that dream. It’s a very special time to live in.

I want to close with a quote from Douglas Engelbart’s Augmenting Human Intellect (1962), which captures perfectly how I see AI transforming learning. Put simply: many high-level methods of learning and problem solving only become feasible once the low-level capabilities are fast and efficient. Thanks to AI, those low-level capabilities are now faster and more efficient than ever.

A direct new innovation in one particular capability can have far-reaching effects throughout the rest of your capability hierarchy. A change can propagate up through the capability hierarchy; higher-order capabilities that can utilize the initially changed capability can now reorganize to take special advantage of this change and of the intermediate higher-capability changes. A change can propagate down through the hierarchy as a result of new capabilities at the high level and modification possibilities latent in lower levels. These latent capabilities may previously have been unusable in the hierarchy and become usable because of the new capability at the higher level.

[…] To our objective of deriving orientation about possibilities for actively pursuing an increase in human intellectual effectiveness, it is important to realize that we must be prepared to pursue such new-possibility chains throughout the entire capability hierarchy (calling for a system approach). It is also important to realize that we must be oriented to the synthesis of new capabilities from reorganization of other capabilities, both old and new, that exist throughout the hierarchy (calling for a “system-engineering” approach).

Appendix: How to Find the Best Books and Legal PDFs

When learning a new subject, one of the most underrated yet critical steps is choosing the right source. If you’re about to spend 20+ hours with a book over the next few weeks, taking time to research which one to read is an investment that pays off.

When searching for a book — whether it’s a textbook or something else — I always start by asking AI. A well-crafted prompt makes a big difference. The good news is that you don’t need to be an expert at writing prompts. Instead, you can ask AI to help you design one. For example, I might begin with something like:

If I want to ask AI to find the best possible textbook to study machine learning, what is the best possible prompt I should use?

After a few back-and-forth iterations, I might end up with something like this:

You are an expert machine learning researcher and teacher. I want to find the single best textbook to study machine learning. Please first identify the major schools of thought in machine learning (for example: statistical learning, probabilistic modeling, deep learning, theoretical/computational learning theory, etc.). For each school, recommend the single most authoritative and pedagogically effective textbook, and explain why it best represents that school.

Then, compare these schools in terms of:

- their importance in modern ML,

- how well they balance intuition and rigorous mathematical explanation, and

- long-term value for building deep expertise.

Finally, reason through the trade-offs and recommend which school I should start with, and therefore which textbook I should study first, making clear why it is the optimal choice for my background and learning style.

Once you’ve finalized a prompt, send it to the best available model and enable “thinking” mode. Lately, I’ve been using GPT-5 Thinking as my go-to, though the best model tends to change every few months.

Don’t accept the first AI answer blindly. Here are some ways to cross-check:

Ask multiple models and see which books are mentioned repeatedly.

Research the authors. Are they leading figures in their field? Are they professors at top universities or major contributors in industry? What are their most important works?

Check usage. Is the book used as a textbook in top university courses?

Look for community feedback. Browse Goodreads, Reddit, or other forums — do readers find it valuable and readable?

Ask experts or friends you trust who are strong in the subject.

A useful rule of thumb when picking a book: choose one that feels just slightly out of reach. Ideally, it should be the kind of book you’d find too difficult to tackle alone, but manageable with guidance from a PhD-level tutor.

If you need AI for every single sentence, the book is probably too advanced.

If you need AI only once every few paragraphs, that’s manageable — what used to be inaccessible is now within reach.

Once you’ve chosen your book(s), check whether they’re available as legal, open-access PDFs.

Project Gutenberg offers over 75,000 classic works in literature, philosophy, science, and other fields that are in the public domain.

For CS/Math, FreeTechBooks is an excellent resource. All the books listed on the site are hosted on websites belonging to the authors or publishers.

Some classic works have dedicated websites. For example, The Feynman Lectures on Physics and all of Hume’s writings are available on well-designed sites.

It’s also worth checking the authors’ personal websites. Many share free copies of the textbooks they’ve written.

If no PDFs are available, another option is to buy a book scanner. You can purchase the book, scan it into a PDF for personal study, and use it strictly for educational purposes — just be sure to comply with your country’s copyright laws.